An article by

Andreas Wegmann

Published on

23/06/2022

Updated on

23/06/2022

Reading time

3 min

Table of content

“You can prove anything with statistics, even the opposite” is a quote from James Callaghan. There are also countless statistics in the field of “payment” and very few of them are actually helpful. The players in the industry like to “prove” their own (often supposed) market leadership or consulting companies publish international studies to prove their payment competence.

Who benefits from payment statistics?

Many online merchants regularly ask themselves whether they could achieve even more sales with the right “payment mix”. Especially abroad, the assessment is often difficult, if other payment methods are used there. But also all kinds of financial service providers try to discover market potentials for themselves with the help of payment statistics or to convince investors of business ideas.

What is Payment?

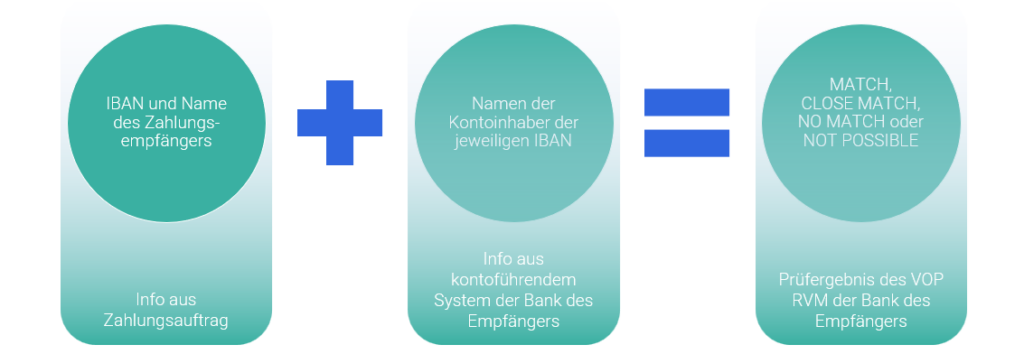

One difficulty with payment statistics is the fuzzy terminology. Authors often define terms differently than readers, which naturally leads to misinterpretations. A good example is the term “mobile payment”. Does it depend on my cell phone operating system or my cell phone provider? If I put my credit card data into my cell phone, is that now a “mobile payment” or a credit card payment?

Another example is the term “direct debit”: in the credit card world this is understood as a transaction with an account without bank overdraft, while in the SEPA world it means that the funds will be pulled (as opposed to push: SEPA credit transfer). In international statistics, the terms almost always become blurred.

Often the statistics are already useless because of other deficiencies, e.g. if only percentage changes are given without a reference to transaction volume or transaction amount. There are “market leaders” in both segments and, if necessary, the figures can also be cross-referenced with industry, association or other criteria. In some niche, almost every player is its own world champion.

The seven lives of a payment transaction

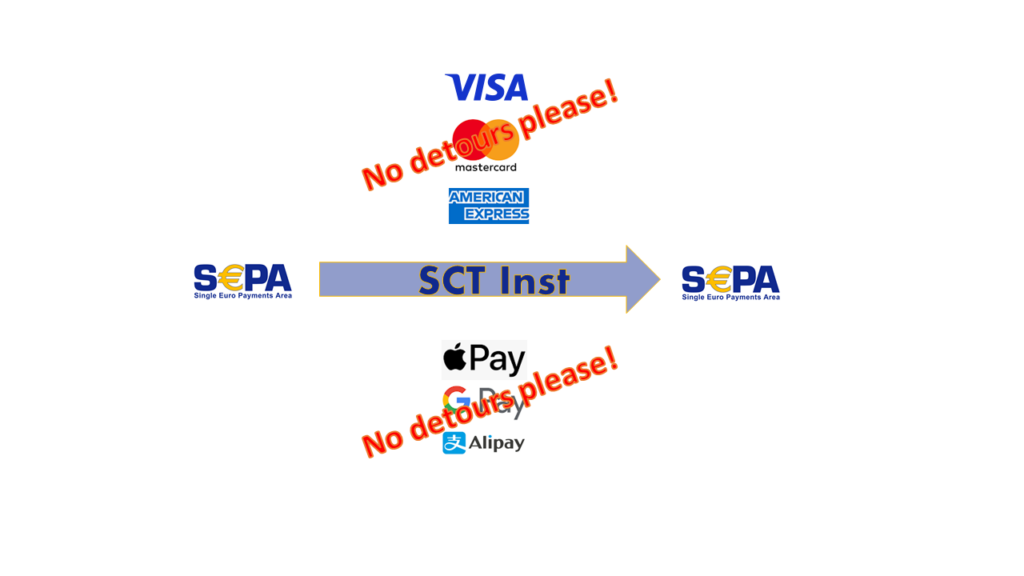

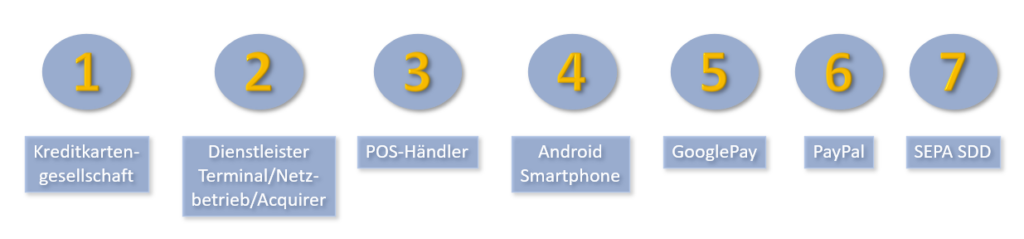

A payment transaction chain passes through many stations until money actually is settled in the recipients bank account. Each of these stations (=companies) may make its own statistics and the market suddenly appears larger than it actually is. A Google Pay transaction at the point of sale is a great example of how a single transaction can multiply sevenfold:

The causal transaction takes place at a card terminal (3) with an Android cell phone (4). Google Pay (5) is activated here, which uses the NFC interface (MasterPass technology as with the iPhone/ApplePay) to establish wireless communication with the terminal and make the payment at the card terminal look like a credit card transaction. For the merchant, it is therefore a credit card transaction that he reports, for example, to the retail association for statistical purposes.

The merchant’s service provider (2), who is responsible for the card terminal and possibly also for card acceptance, of course also records the credit card transaction for its own statistics. Ultimately, the transaction still ends up in the card company’s statistics (1).

More interesting is the way on the other half of the picture: if no credit card is deposited with Google Pay, but PayPal (6), PayPal acts as the so-called card issuer and receives the so-called “interchange fee” of the credit card world. In fact PayPal does the clearing in the interbank transaction processing: the transaction amount is collected from the buyer’s account as SEPA direct debit (7). Thus, the transaction can be found in the statistics of the ECB, but not as a card transaction, but as a SEPA direct debit.

How do you read statistics correctly?

Answer: it is best not to read them at all if the authors do not provide all the information on the survey at the same time and clearly clarify the terms. If annual statistics are published and the collection of data remains clear and unchanged, valid conclusions can be drawn. ibi Research, for example, does an exemplary job here, because the authors there work with scientific methodology and, above all, independently.

Conclusion: If you want to use statistics, it is better to first consider the facts to be proven and then look for the appropriate statistics.

Share